Understanding Knee Mechanics

- Dec 14, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated November 2019

Injuries can be overwhelming and understanding how to protect or rehabilitate injured structures can be confusing. With solid anatomical knowledge of the injured area, you can better help yourself perform the correct rehabilitation to come back stronger and more confidently to your daily sports and activities. Medical professionals will often talk about the anatomical structures involved in your injury, but what do these terms mean? The purpose of this article is to discuss the anatomy of the knee so that you can better understand its mechanics.

The Knee

The knee is one of the strongest, most stable joints in the body. While it is commonly understood as a single unit, it actually has two joints, three compartments, and can move in a variety of ways.

The two joints are the tibiofemoral joint where the tibia and the femur articulate, and the patellofemoral joint which consists of the patella (kneecap) that rides in the trochlear groove in the distal femur:

The tibiofemoral joint is comprised of two compartments, lateral and medial. It is these compartments, and most commonly the medial one, that are implicated in knee osteoarthritis. The tibiofemoral joint allows for knee flexion (bending) and extension (straightening), as well as very small amount of rotation, compression and distraction, and lateral movement.

The patellofemoral joint contains a single compartment, and can also be subject to osteoarthritis. It improves the ability of the quadriceps muscle group to extend the knee and offers some bony protection to the anterior tibiofemoral joint.

Image retrieved from: https://www.peternelsonfitness.co.uk/blog/2018/3/19/how-to-improve-knee-strength-and-stability

Muscles and Tendons

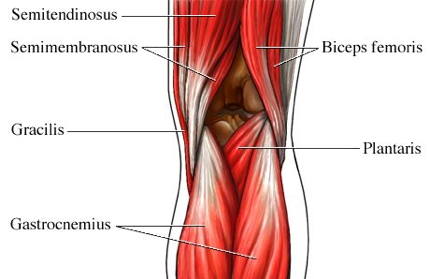

A large number of muscles act on the knee and their associated tendons cross the front and back of the joint. The primary muscle groups that move your knee are the four muscles comprising the quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and vastus medialis), and the three muscles comprising the hamstrings (semitendinosus, semimembranosus and biceps femoris).

The primary functions of muscles are to cause joint movement and provide dynamic stability and shock absorption. All four quadriceps muscles converge to become the quadriceps tendon which then becomes the patellar tendon before inserting into the tibial tuberosity.

The patella is a sesamoid bone, meaning that it is partially embedded inside the quads/patellar tendon. The hamstrings muscles cross the posterior corners of the knee and attach to the tibia or the head of the fibula. Hamstrings are primarily responsible for knee flexion. Sometimes, during ACL reconstruction surgery (ACLR), the tendon of semitendinosis is harvested to use as the ACL graft. This is known as an autograft - ‘auto-’, a prefix meaning ‘self’. One further muscle, a calf muscle named the gastrocnemius, also contributes weakly to knee flexion.

Images retrieved from: https://ohiodance.org/dance-education/dance-wellness/knee-anatomy/

Knee Cartilage:

Two main types of cartilage exist in the knee.

Hyaline cartilage, also known as articular cartilage, refers to the layer of cartilage covering the load bearing surfaces of bones in a synovial joint. It is firm and avascular and allow for smooth articulation of two bones. In the case of the knee, articular cartilage exists on the distal end of the femur, proximal end of the tibia and on the posterior aspect of the patella. Friction caused by patellar cartilage rubbing on the distal femur can cause fine crackling/popping known as crepitus. This most commonly occurs under load, such as when standing from a deep squat. This is not typically indication of an injury, rather, that friction is causing a rapid catch/release phenomenon of the patella on the femur.

Image retrieved from: http://josephbermanmd.com/anatomy-of-the-knee/articular-cartilage/

The meniscus refers to a different type of cartilage within the knee. It is loosely attached to the tibial plateau and sits between the tibia and femur and assists in shock absorption. In each knee, there are two C-shaped menisci. The medial meniscus sits towards to midline of the body, and the lateral meniscus sits towards the outside of the body. In addition to aiding in shock absorption, the menisci improve congruence between the femur and the tibia thus distributing body weight over a larger surface area.

Knee Ligaments

Ligaments refer to tough bands of connective tissue that connect two bones together. Their primary function is to provide passive stability for a joint. When referring to the knee, four main ligaments are considered: the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), and the medial collateral ligament (MCL).

The cruciate ligaments (ACL and PCL), form an x-shape within the knee joint and control the forward and backward movements of the tibia in relationship to the femur respectively, as well as providing some resistance to knee rotation.

The collateral ligaments (MCL and LCL), span the medial and lateral sides of the knee and provide stability against valgus and varus movements of the tibia. One can think of knee valgus as gapping the medial edge of the knee as in someone who is knock kneed, and varus as gapping the lateral edge of the knee as in someone who is bow legged.

ACL tears often occur with meniscus damage and minor MCL tears.

Picture retrieved from: http://sibere.co/acl-mcl-repair-surgery.html

If you're experiencing any pain in your knee(s), book an appointment today so we can help you find the root of the issue, and recover fast.

Stephen Baker graduated from Western University with a Masters of Physical Therapy. He has a passion for helping those with neck, hand or knee injuries return to their daily adventures. Book with Stephen today.

.png)

Comments